Bat myths – where did they come from and what can we do about it?

There are many cultural beliefs associated with bats. While not disliked or mistrusted by all, bats – to their detriment – have been the subject of myths and legends in many cultures for hundreds or indeed, thousands of years.

Their “unusual” physical form

Myths and legends frequently associate bats with darkness and evil. This negative attitude towards bats is thought to stem from the difficulty many people find in comprehending their “unusual” physical form. Seen as ambiguous creatures, both flying like birds and also possessing hair and teeth like mammals, bats are an animal people struggle to identify with as their appearance is so different from more “normal” animals. This, along with their nocturnal lifestyle and unusual roosting habits, has led to many of the myths associating bats with evil or deceit.

Stretching the truth for a good story

Myths tell us bats are scary and dangerous. This theme is found in beliefs such as; bats will drink your blood, get stuck in your hair, will deliberately attack you or will put you at great danger from disease. While several of these myths may be based on fact, for the most part these myths are false or grossly exaggerate the truth.

For example there are only three species of vampire bat (out of 1300+ bat species found worldwide) that do drink blood, and all three are only found in Central and South America.

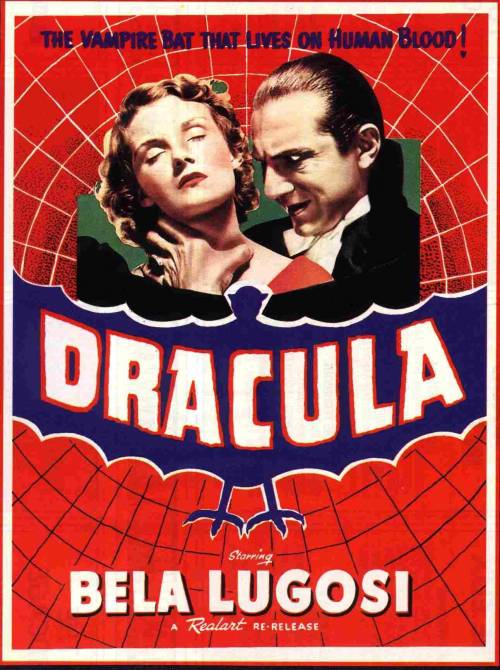

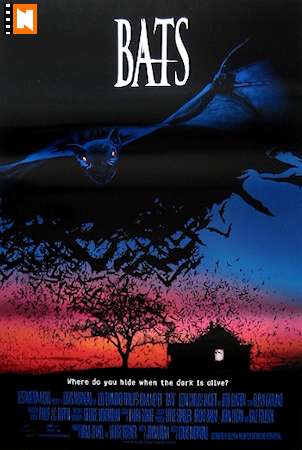

While bats will not get stuck in your hair or deliberately attack you, they are known to carry diseases that can infect humans, however this could be said of many species including the cats and dogs we share our homes with. Many of these myths have been perpetuated through literature, film and old wives tales. Works from famous writers such as William Shakespeare and Bram Stoker (author of “Dracula”) have contributed to such myths and legends that perpetuate fear in people, as they associate bats with graveyards, vampires, death and the devil.

Alongside the association of bats with nightmarish themes in literature, bats feature heavily – again with negatively – in everyday phrases across western societies. Phrases such as “blind as a bat”, “bat out of hell” or the use of the term “batty” (meaning silly or even mad) have also contributed to the way people perceive bats. It is this combination of myths, folklore, literature and localized sayings that has most likely led to bats being named as one of the least liked animals, even though most people have never interacted with a bat before.

Myths spread from ancient cultures

Many of these bat myths and legends common in the western world have origins from Ancient Greek, Roman and Egyptian cultures. In ancient Rome, bats were nailed to the door of the house as a protection from witches and diseases. In fact it was believed at that time, that their silent presence announced the arrival of an accident or a great storm.

Interestingly these myths have spread to most western societies even though many countries, particularly those in the southern hemisphere, do not necessarily have the same types of bats as the regions where the myths orginated. Within Chiroptera, the mammal order that encompasses all bats, two distinct groups are found. The first are the small, insect eating bats called Microchiroptera (micro-bats). Bats within this group include those that roost in caves or in tree cavities and are found worldwide.

The second is Megachiroptera (mega-bats), a group that includes all the large bats, including flying-foxes, which predominately eat fruit and nectar. This group is mainly confined to south-east Asia and the Pacific, including India and Australia. The absence of mega-bats from areas in the northern hemisphere from where many of the myths and prejudices were founded indicates that these legends were originally based on misunderstandings of micro-bat species. In many countries like Australia, the use of the generic term “bat” has allowed the extension of these cultural prejudices to encompass mega-bats (including flying-foxes) despite the many physical and ecological differences between them and their smaller counterparts.

So how do we change this negative view towards bats?

Unfortunately conservationists and bat scientists alike face an uphill battle in trying to educate communities about the real nature of these misunderstood creatures. The media is currently our biggest obstacle but ironically it could also be our biggest ally if we could overcome its tendency for sensationalism.

Journalists commonly use links to cultural legends and existing belief systems to make their stories resonate with their audiences. These connections have tremendous power through their symbolism, implied meaning and widespread recognition – that is why sensationalist headlines like “This Terrifying Little Creature Is Actually Much Deadlier Than You Probably Thought” recently published by Upworthy.com attracts so many readers. This combination of culturally engrained beliefs with real-world wildlife problems, such as the spread of zoonotic disease, within media reporting makes it harder not only for the public to separate the two but also for bat advocates to convince journalists to report on these issues without reference these cultural prejudices.

Journalists commonly use links to cultural legends and existing belief systems to make their stories resonate with their audiences. These connections have tremendous power through their symbolism, implied meaning and widespread recognition – that is why sensationalist headlines like “This Terrifying Little Creature Is Actually Much Deadlier Than You Probably Thought” recently published by Upworthy.com attracts so many readers. This combination of culturally engrained beliefs with real-world wildlife problems, such as the spread of zoonotic disease, within media reporting makes it harder not only for the public to separate the two but also for bat advocates to convince journalists to report on these issues without reference these cultural prejudices.

It is up to bat advocates to work with journalists to show them how bat stories can be just as fascinating to their audiences without references to common myths and legends. The real world of bats is much more captivating than any old wives tale could ever be. We just need to show them.